Is there such a thing as a scientific movie?

Recently, I have been dealing with the question of whether a film is capable of conveying scientific knowledge. By this, I do not mean the more or less reputable science programs on television, which tend to contribute to the popularization of scientific knowledge. Nor do I mean film as the object of scientific study in film studies. Rather, I am concerned with the question of whether film can adequately convey a scientific, controversial subject matter. The starting point for this was a study that has not yet been published and that was conducted in the Department of Education at the University of Trier: a comparison of the teaching methods of film and text in terms of their effectiveness in learning when dealing with scientific knowledge.

Theoretische Preliminary considerations

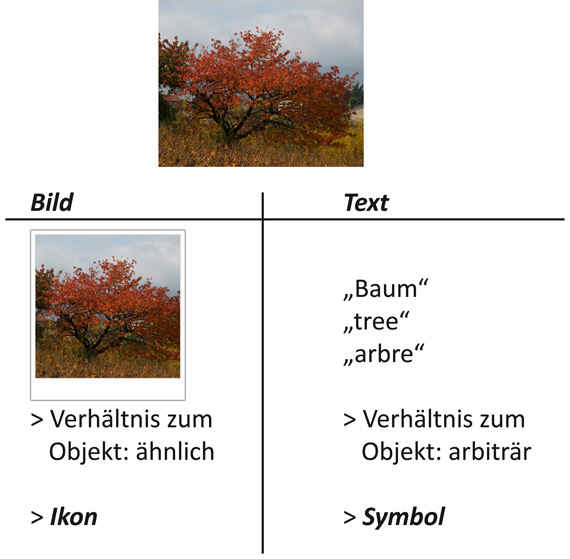

At the outset, I would like to simplify things theoretically: for the time being, film will be understood as a kind of image. Comparisons between text and images are very common in history, opinions fluctuate between image or visualization optimists (e.g. Otto Neurath) and image or visualization pessimists (e.g. Neil Postman). The basic assumption underlying these comparisons is that there is a fundamental difference between text and images. But what is this fundamental difference? Semiotics can provide valuable insights for this question (see Schnotz 2005, Joly 2006). Figure 1 shows a simple diagram: according to this view, images show a similarity to the object and are called “icons”; text, on the other hand, is not similar to an object, it is arbitrary and is called a “symbol”.

Applied to film, this means that film has a relationship to reality (> Ikon). What does this relationship to reality look like?

In early film theory, there was a dispute about the nature of film based on its relationship to reality: Is film more realistic/documentary or more illusionistic/artistic?

- “documentary character” position (e.g. Kracauer 1960): film is fundamentally documentary, depicts reality, no interventions

- “artistic character” position (e.g. Arnheim 2002 [original 1932]): film ≠ mere mechanical reproduction of reality, but an art form in its own right

Within these discussions, numerous theories develop that examine the essence of film. These theories are largely not empirically proven, as they are aesthetic-hermeneutic in nature.

The Aesthetics and Essence of Film

In my opinion, it can be helpful to learn about the aesthetic qualities of a film in order to get to its essence. The key question here is: What distinguishes film from all other media? What is typically cinematic? James Monaco (2004, 162) writes in relation to film:

The result is, as Christian Metz says: ‘As a simple art, film is constantly in danger of falling victim to its simplicity’.” Film is too easy to understand, which makes it difficult to analyze. ‘A film is difficult to explain because it is easy to understand.’

In film theory, the essence of film is considered to be determined primarily by two elements: mise en scène (comparable to photography) and montage.

- Mise en Scène: French for “staged”, refers to the camera’s possibilities of influence (image detail, shot size, shooting angle, etc.). In the film “Citizen Kane”, for example, media mogul Kane runs for an election that he seems certain to win, but then a scandal costs him the election victory. The lopsided camera position (example image at WikiCommons suggests from the outset that something is wrong with Kane.

- Montage: temporal sequence of images, the viewer relates them to what has already been seen. The Soviet film director Kuleshov was able to demonstrate this process of relating by combining an identical shot of an actor with various other scenes (eating, a funeral, beautiful women, etc.): the viewers claimed that the expression of the actor matched the mood of the images (hunger, mourning, passion, etc.), even though it was always identical (example by Mike Jones, please scroll down).

The user constructs the meaning of the film based on these aesthetic means and their personal interpretations and viewing habits. Some viewing habits are generally valid (= cinematic conventions), e.g. sequence “house from the outside” + “person in a house” = interpretation “person is in the house from before”.

Preliminary conclusion: film has something to do with reality, but at the same time it is also artistic and illusionistic. Meanings in film are, therefore, complex phenomena, since factors from mise en scène, montage, viewing habits, etc. all interact. However, science (and thus scientific film as well) demands statements that are as unambiguous as possible. Can we make such unambiguous statements in film? If so, it would be necessary to ensure that the chosen means are really received by the viewer as intended. A look at research that deals with the effect of films and images on the viewer could help here.

Research on reception and media effects

The saying goes: “A picture is worth a thousand words”. But is this saying true? Does a picture even live up to this high standard?

In November 1988, Philipp Jenninger, then President of the Bundestag, gave a speech on the “Reichsprogromnacht”, which was misunderstood and ultimately cost him his job. Ida Ehre, a well-paid Jewish actress and director who had survived the Holocaust and subsequently excelled in the cultural field, was present in the hall. A little later, a symbolic image went through the press showing her alleged consternation after Jenninger’s speech. The majority of recipients understood the picture that way – after all, it is clear to see. In fact, however, Ida Ehre was merely unwell and, according to her, did not even notice the speech.

“No image is self-explanatory,” says Gombrich (quoted from Weidenmann 1994, 23): the meanings of images depend on explanations and the prior knowledge of the viewer. That is why no image appears in the press without a caption. Film is also a convergent medium: it also combines other media, such as language. Language could therefore take on the task of classifying the images shown. But how do language and images relate to each other in film?

The term “text-image gap” could be helpful here: text can support the image message, but it can also contradict it. Text and image can thus, to a certain extent, overlap (like closed scissors) or diverge (like open scissors). However, the term is also problematic because it suggests that text and image in a film are two separate units that are related to each other. However, the language level and the image level explain each other (see Holly 2006). It may be difficult to analyze these two levels independently of each other without reducing their meaning.

Studies of reception from a more psychological perspective point in a similar direction. “Image and sound together are the input variables for the cognitive system of the recipient,” writes Strittmatter (1994, 178; translated by me). What role do text and image play in this?

The central idea (see Strittmatter 1994) in this context is: text and image are not only different channels, but also have different contents (Marshall McLuhan: “The Medium is the Message”). The image is considered to be richer in information and serves as a means of orientation. The text, on the other hand, is more abstract, but is therefore able to categorize and direct attention.

On the one hand, language controls the processing of images by selecting certain aspects of the image and emphasizing them; on the other hand, interference can also occur when text and images are processed together

Reception is thus more of an active process than the mere “reading” of information. Images do not simply express something that they carry within them; rather, they must be read, decoded – but the recipient always plays a crucial role in this process.

Conclusion and theses

On the basis of the insights just outlined, my thesis is that film, due to its very own cinematic means, is hardly able to convey abstract, factually “correct” knowledge, as required by science (cf. Bühl 1984). Its stylistic devices are aesthetic and artistic in nature and therefore, in principle, open to interpretation. The effects can (and in practice are) minimized by, for example, deliberately filming only from the front. But even a documentary film is not completely neutral, because a multitude of aesthetic decisions remain (e.g. the pure selection of scenes: what is actually shown, what is cut out?).

I am aware of three limitations that could weaken or jeopardize my thesis.

- strength of film = media convergence: film can compensate for its shortcomings by integrating other media, e.g. speech and graphics; it then provides supporting images for what is being said. However, the question then becomes problematic what to do when there are no supporting images, for example because the process is very abstract or very complex. Furthermore, when images and language are combined, the question arises as to which of the two parties is conveying the information. Peeck 1994, for example, distinguished between information conveyed by images, information conveyed by language, and information conveyed by both media. From an educational point of view, it is also important to consider how the image affects the understanding of the spoken text: it could promote or prevent learning, or have a completely neutral effect. This question is, of course, all the more important when a purely symbolic image (such as of politicians shaking hands) is used to illustrate a non-visualizable topic.

- Do films speak of the truth in a different register than science (cf. Corcuff 2008)? The term “register” comes from linguistics and refers to socially based differences in language (e.g. a comparison of a conversation between an employee and their superior with a conversation between employees about the same topic). Corcuff uses the term to support the thesis that cinematic truths cannot be compared with truths from science (e.g. sociology), but are nevertheless not untrue.

- In my previous considerations, I assumed that language is rather unambiguous, but images rather ambiguous. In fact, unambiguous language and terms are one of the central requirements for scientific texts. But is this assumption correct at all?

Comments on my considerations – especially critical ones – are welcome!

References

- Arnheim, Rudolf (2002): Film als Kunst. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Balázs, Béla (2001): Der Geist des Films. 1. Auflage. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Barthes, Roland (1964): Rhétorique de l’image. In: Communications, H. 4.

- Bonfadelli, Heinz (2004): Medienwirkungsforschung I. Grundlagen und theoretische Perspektiven: UTB.

- Bonfadelli, Heinz (2004): Medienwirkungsforschung II. Anwendungen in Politik, Wirtschaft und Kultur: UTB.

- Bühl, Walter (1984): Die Ordnung des Wissens. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

- Corcuff, Philippe (2008): Philosophie, sciences sociales et cinéma. Cours d’ouverture. Unveröffentlichtes Manuskript zum Kurs am IEP Lyon.

- Corcuff, Philippe (2004): La société de verre. Pour une éthique de la fragilité. Paris: Armand Colin (Collection Individu et Société).

- Dorn, Margit (2003): Film. In: Hickethier, Knut (Hg.): Einführung in die Medienwissenschaft. Stuttgart u.a.: Metzler, S. 201–219.

- Hickethier, Knut (Hg.) (2003): Einführung in die Medienwissenschaft. Stuttgart u.a.: Metzler.

- Holly, Werner (2006): Mit Worten sehen. Audiovisuelle Bedeutungskonstitution und Muster transkriptiver Logik in der Fernsehberichterstattung. In: Deutsche Sprache, Jg. 34, H. 1-2, S. 135–150.

- Joly, Martine (2006): Introduction à l’analyse de l’image. Paris: Armand Colin (image 128).

- Kracauer, Siegfried (1960): Theory of Film. The Redemption of Physical Reality: Oxford University Press.

- Mayer, Richard (Hg.) (2005): The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning: Cambridge University Press.

- Monaco, James (2004): Film verstehen. Kunst, Technik, Sprache, Geschichte und Theorie des Films und der Medien ; mit einer Einführung in Multimedia. 5. Aufl., überarb. und erw. Neuausg., dt. Erstausg. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verl. (rororo rororo Sachbuch, 60657).

- Peeck, J. (1994): Wissenserwerb mit darstellenden Bildern. In: Weidenmann, Bernd (Hg.): Wissenserwerb mit Bildern. Instruktionale Bilder in Printmedien, Film/Video und Computerprogrammen. Bern: Huber, S. 59–94.

- Peters, Jan Marie (1995): Theorie und Praxis der Filmmontage von Griffith bis heute. In: Beller, Hans (Hg.): Handbuch der Filmmontage. München, S. 33–49.

- Postman, Neil (2006): Wir amüsieren uns zu Tode. Urteilsbildung im Zeitalter der Unterhaltungsindustrie. 17. Aufl… Frankfurt am Main: Fischer (Fischer, 4285).

- Schnotz, Wolfgang (2005): An Integrated Model of Text and Picture Comprehension. In: Mayer, Richard (Hg.): The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning: Cambridge University Press, S. 49–69.

- Strittmatter, Peter (1994): Wissenserwerb mit Bilder bei Film und Fernsehen. In: Weidenmann, Bernd (Hg.): Wissenserwerb mit Bildern. Instruktionale Bilder in Printmedien, Film/Video und Computerprogrammen. Bern: Huber, S. 177–194.

- Weidenmann, Bernd (Hg.) (1994): Wissenserwerb mit Bildern. Instruktionale Bilder in Printmedien, Film/Video und Computerprogrammen. Bern: Huber.