Portraits and daguerreotypes: new inspiration

What makes a good portrait? After I already exhibited some theses on portrait photography a few weeks ago, Jeff Curto’s podcast “The History of Photography” gave me further ideas. Curto, who is also responsible for the podcast Camera Position on the creative aspects of photography, discusses one of the early forms of photography: the daguerreotype.

The daguerreotype as a photographic process

The daguerreotype was developed in 1839 by Louis Daguerre (after extensive preliminary work by Joseph Nicéphore Nièpce). The image was fixed on a plate coated with a chemical compound of silver and halogens and then developed under mercury vapor. The silver gives a daguerreotype an attractive sheen, but also means that the image can only be seen clearly from a certain viewing angle.

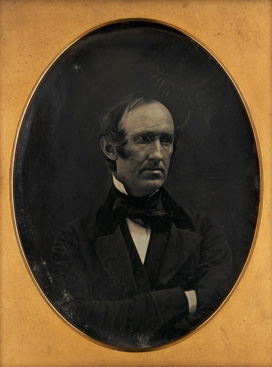

As a result, daguerreotypes are incredibly detailed and sharp. Each shot is unique and cannot be duplicated. In the 1840s and 1850s, daguerreotypes were very popular because they were cheaper than a painted portrait and more detailed than other photographic processes (such as the talbotype). The example image is a daguerreotype of Wendell Philips, made around 1850 by Southworth and Hawes (taken from the Flickr page of the Boston Public Library, published under a Creative Commons Attribution license).

Southworth and Hawes: early pioneers of portrait photography

Daguerreotypes were a medium for portraits. People had themselves photographed in silver en masse. The temptation to overcome spatial and temporal distances through photography was too great, as was the idea of a person always being present (even if only in an image).

The Boston duo Albert Sands Southworth and Josiah Joseph Hawes, active daguerreotypists from 1843 to 1862, exemplify the range – and still today provide inspiration for what a good portrait should look like. And so they inspired me to expand my five suggestions a little. Numerous examples of their work can be found at the American Museum of Photography.

The expression: the central means of expression

I still believe that you have to know a person to take a good picture of them, but today this statement seems a bit too imprecise to me. After all, a person is always much more than could ever be expressed in a photograph. So there is no choice but to pick out one aspect – preferably the most representative one possible – and depict it. And so the expression on the subject’s face becomes an important design tool that can be reinforced by other elements:

Expression is everything in a daguerreotype. All else,—the hair —jewelry —lace-work —drapery or dress, and attitude, are only aids to expression. It must at least be comfortable, and ought to be amiable. It ought also to be sensible, spirited and dignified, and usually with care and patience may be so.

The role of the photographer: playing with light

Light is what makes photography possible in the first place, but at the same time it comprehensively defines its message. A. S. Southworth suggests an interesting exercise in this regard: “Learn to look and see the difference under different lights in the same faces. Learn to see the fine points in every face, for the plainest faces in the world are human faces, belonging to human beings…”

A game with light – and different types of lighting – can help us to reinforce the desired message. From this point of view, a good sense of lighting seems to be much more important for a photographer than technical requirements – these are merely a means to an end.

Authenticity as a goal?

It should be the aim of the artist-photographer to produce in the likeness the best possible character and finest expression of which that particular face or figure could ever have been capable. But in the result there is to be no departure from truth in the delineation and representation of beauty, and expression, and character.

A photograph is always a photograph of something or someone. So it always makes a statement about what it represents. If we believe that portraits should make a statement about a person, we must therefore strive for authenticity: our shot must not imply anything that does not fit with the person depicted. And so, in his world-famous book Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes reads character traits from a person’s portrait.

But is a portrait necessarily limited to this “documentary” area of photography? Or can it say more, tell stories, show possibilities that a person is not aware of? Rike pointed out this play with roles and staged atmospheres in the comments on my last post. What do you think?

To be continued…

Since my little historical excursion has proven to be valuable in my eyes, I will blog about what history can teach us about contemporary portraits in future posts. So it remains exciting.