Portfolios in user experience (UX) Making a skillful impression with a UX portfolio

Regardless of whether they are employed or self-employed: When user experience professionals apply for a job or want to acquire new clients, they often have to present a portfolio. But what exactly is a portfolio in user experience (UX)? Which skills are important? And how can you create a UX portfolio that really convinces hiring managers or potential clients?

When hearing the word “portfolio”, UX professionals often think of a fancy website with little text and lots of visually impressive work samples. Such portfolios are typical for visual design and user interface (UI) design. They show the finished, visually polished result as evidence of the designer’s skills.

“Of course, UI designers should show that they master timing, colors, interactions, and animations,” explains Sebastian Baum, a UX professional who organizes regular round tables in Cologne for portfolio feedback rounds. Visual design skills are crucial for designers who are responsible for the interface design of digital products. However, many other factors play a role in the user experience (UX), i.e. the actual impact that a design has on the audience, which requires other skills. Sebastian Baum warns: “This is a common pitfall: many UX professionals also want these kinds of small animations, even though they distract from their core skills rather than helping them achieve their goals.”

Core skills for UX jobs

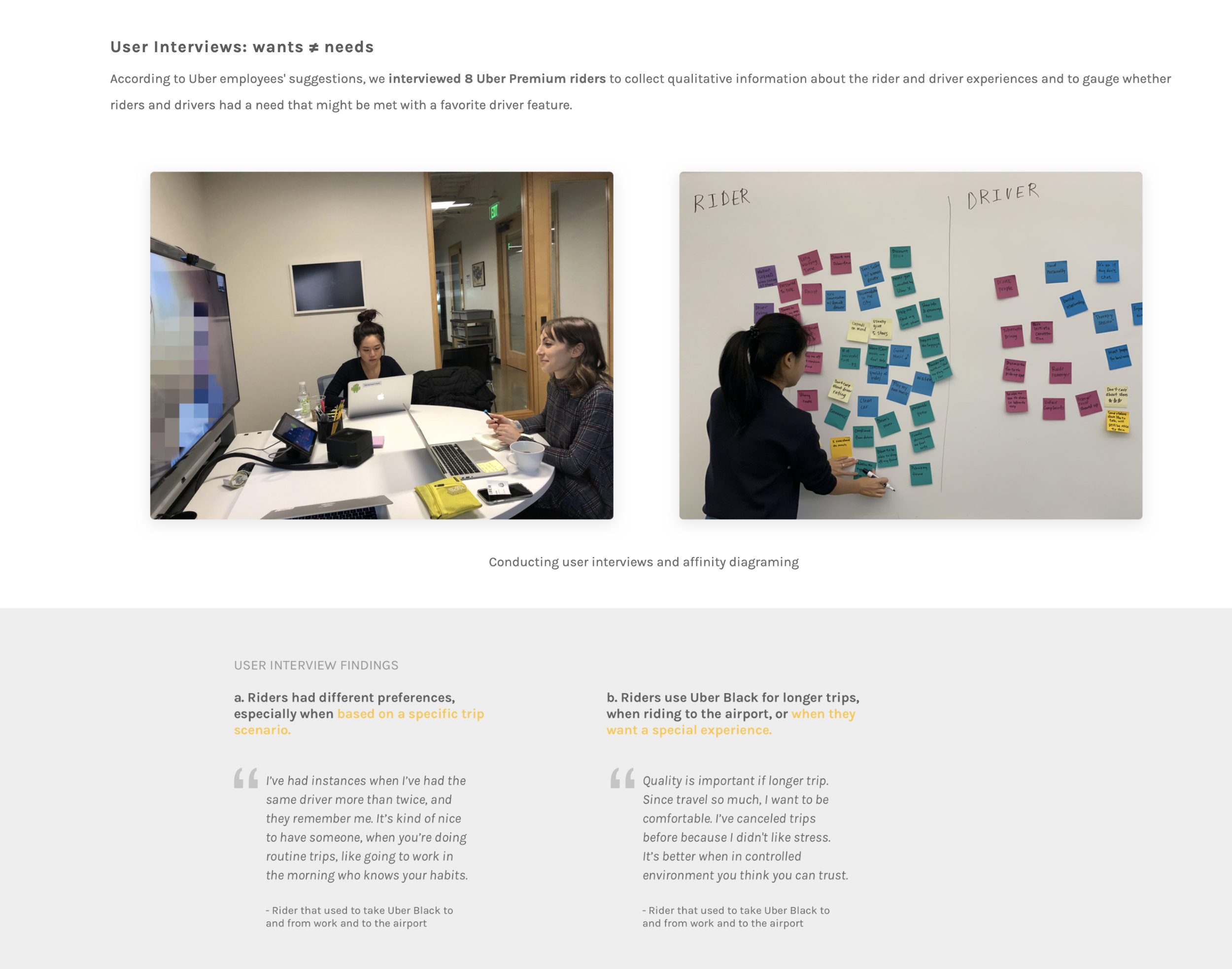

But what exactly are these core skills that UX professionals need? This depends in particular on the profile and the type of job or assignment. Visual design skills are particularly relevant in the UI sector. For UX design, user research, or UX management, the creative process with its intermediate steps and failed attempts is more important than the visual end result: How exactly did you ensure that the created product meets the user needs and generates value? This is where knowing prototyping tools (such as Figma, XD, Axure, or Sketch), research methods (such as interviews, observations, or usability tests) and methods for analyzing user needs (such as affinity diagrams) and communicating them (such as personas or customer journey maps) are important. There are also important overarching skills for all UX jobs, such as empathy, collaboration, creativity and problem-solving skills. A UX portfolio is, therefore, often more content-heavy than a visual portfolio because more background information and explanations are required.

It is also important to put yourself in the shoes of the HR managers. They want to know how UX work creates value for users and the organization. “It is very important to show the return on investment of UX,” confirms Sebastian Baum. “I know that this is incredibly difficult, but that is the power of UX: it can improve the status quo. And if you can present this to the recruiter or Head of UX, you will quickly be on the short-list.”

However, UX professionals should not forget that a portfolio must appeal to different audiences. “As a UX professional, I usually know UX methods,” explains Sebastian Baum. “That means you do not have to explain to me how it works, but what you got out of the method.” However, there are many companies without UX professionals deciding on staff, or companies where human resources (HR) and management make a pre-selection. “Storytelling is one of our great assets in UX design,” says Sebastian Baum, explaining his solution strategy. “Processing information in such a way that both audiences understand what you are doing.”

Building a portfolio

Therefore, a portfolio should demonstrate your skills meaningfully, match your personality and the desired job, and show how your work creates value. This works very well with case studies based on your projects. Typically, UX portfolios contain three to five case studies, but more important than the number is that each case study demonstrates relevant skills. Depending on your profile and the intended goal, different projects are suited to build a portfolio: Research projects, concepts, training courses, publications, lectures, digital products, and much more.

“It is difficult to remember what you did in a project that lasted months after years,” explains Sebastian Baum. “And therefore, it is best to write down the entire process immediately. I have set up a structure for this: How long was the project? What is the goal? What is the problem and how did I solve it? What were the results?”

Based on such records, start to think a little about yourself: What exactly are your strengths and what sets you apart from other UX professionals? What interesting stories can you tell about your projects? The results of this self-reflection also look very good as “lessons learned” within a portfolio.

But what content should the case studies present? The STAR method is a good way to do this:

- Situation (S): relevant contextual information

- Tasks (T): Description of the core problem and your role (also in interaction with other people involved in the project)

- Actions (A): Approach to solving the problem, including selection and justification of the chosen methods

- Results (R): Results of the project with key figures, for example as graphics, metrics or quotes from studies and tests with users.

UX professionals should not be afraid of authentic representations of their intermediate steps: sketches, notes, and white boards make a project credible. “A picture of the finished product will say I designed this; I did the visual part,” says Joe Natoli in his course on UX portfolios. “A picture of a sketched process or problem-solving notes says I figured out what the problem was and how to solve it.”

But what should UX professionals do if they do not yet have any projects? “It is perfectly fine to include a fictitious project and mention which methods you used and why,” explains Sebastian Baum. “I want to see if you critically question whether this is really the right method for the situation and why you chose this method in this situation.” If you do not like working on fictitious projects, you can volunteer in non-commercial projects or develop suggestions for improvement for an established company without being commissioned to do so. You should just approach these projects as if they were real assignments.

And what if you have projects but are not allowed to talk about them? This is a common problem because contracts often contain non-disclosure agreements (NDAs). These are intended to prevent sensitive information from projects from becoming public. But there are solutions: UX professionals can seek discussions with clients to find a compromise or make sensitive information illegible. Alternatively, they can create a generic, neutral project based on a real project, which is addressing the same challenge with the same solution approach, but does not show any real documents from the project. In either case, the responsible handling of non-disclosure agreements is a strong point, indicating that a person has integrity.

Presenting portfolios

Once the relevant information for a portfolio is collected, the next question arises: How can UX professionals best present their portfolio? A dedicated website is a very frequent option with many advantages: You can easily share the portfolio via a link, a website is publicly viewable (but can also be password-protected), and there are flexible options for customization. Alternatively or additionally, a PDF presentation or portfolio services such as Behance is useful.

But no matter which format is ultimately chosen, there are a number of tips that UX professionals should take into account:

- keep the focus on the actual work with the help of a sensible structure and a reduced layout,

- provide a short executive summary with the problem, relevant skills, and key findings,

- select case studies that they fit the organization and job description as well as possible,

- document the evolution of the project, including its intermediate steps and discarded ideas,

- ensure that decisions are supported by data,

- share the portfolio with others, gather their feedback, and continuously improve the portfolio.

Conclusion

UX portfolios are just as diverse as the job profiles in the UX industry. It is therefore important to be clear about your core skills and the requirements of the job or assignment. However, with the help of specifically designed case studies, UX professionals can provide a well-founded look behind the scenes of their work and thus prove their skills. Ultimately, the aim is to demonstrate how your (UX) work creates value for users and the organization.

Note: A version of this article in German was published in t3n 77.

Links and References

- Study about UX careers and relevant skills: https://www.nngroup.com/reports/user-experience-careers/

- Tips for UX research portfolios: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ux-researcher-portfolio/

- Creating UX design portfolios: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/uxdesign-portfolios/

- Using the STAR method for UX job interviews: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/answer-ux-job-interview-questions/

- Joe Natoli’s course on portfolios: https://www.udemy.com/course/build-apowerful-ux-portfolio/

- UX portfolio tipps: https://marketsplash.com/de/ux-designer-mappe